2023.04.20 The Nisshinkan School and Rules for Samurai Children

The Aizu samurai were known throughout Japan for their bravery and high moral standards of conduct. The Nisshinkan, a school established in 1803, was the centerpiece of the training system for sons of samurai of the Aizu domain. Nisshinkan was considered the leading educational institution of its type, and even welcomed visits from samurai in other domains who were eager to learn from the Aizu samurai.

The school grounds, which covered around 26,500 square meters, was once located adjacent to Tsuruga Castle. The school was destroyed during the Boshin War (1868–1869) but was faithfully recreated in 1987 on the current site using the original design and scale. The facility is open to visitors, who can learn about the samurai youth through detailed dioramas and exhibitions about student life. Highlights include the martial arts training hall, a pond that served as Japan’s oldest swimming pool, and an observatory where students learned about astronomy.

Boys usually entered the school from ten years old after attending preparatory classes between the ages of six and nine. They progressed through the ranks, graduating in their late teens. Students received an all-round education to prepare them mentally, physically, and spiritually for a life of service to their lord and their community. Core principles of the training, such as respecting others and taking responsibility for one’s actions, are still reflected in Aizu’s educational values today.

High ideals and first-class facilities

As life in Japan became relatively peaceful in the Edo period (1603–1867), leaders grew concerned at a relaxation of manners and behavior. Tanaka Harunaka, the chief advisor of daimyo lord Matsudaira Katanobu (1744–1805), suggested placing greater emphasis on educating the next generation. A wealthy kimono merchant provided most of the money to build Nisshinkan, and members of the community, including officials, scholars, and students, worked side by side during the five-year construction period leading up to the opening in 1803.

The school’s enrollment was between 1,000 and 1,300 students at any one time. The day began at 8 a.m., and the boys studied a wide range of subjects, including reading, calligraphy, ethics, etiquette, religion, astronomy, and even physiology, according to their age and grade. Those who excelled in their studies, along with the eldest sons of families with sufficient wealth, could then move on to the school’s division of higher education.

All students and teachers were provided with a simple but filling lunch. This was the forerunner of the modern kyushoku (school lunch) system, in which a nutritious hot lunch is served at public elementary and junior high schools nationwide. Nisshinkan students practiced swordsmanship, archery, horseback riding, and swimming in the Suiren-Suiba Pond, which was the equivalent of a school pool. Among the practical lessons was how to master a river crossing on horseback while dressed in heavy armor.

The students were also taught how to end their own life with their sword, should the need arise. Nineteen members of the Byakkotai (White Tiger Brigade) who attended Nisshinkan utilized this aspect of their training on Mt. Iimori during the Battle of Aizu in 1868, when they took their own lives rather than face capture by enemy forces.

All students, regardless of age or grade, were required to uphold samurai ideals. These included treating adults and senior students with respect, taking care with one’s appearance and speech, and conducting oneself appropriately at all times in public.

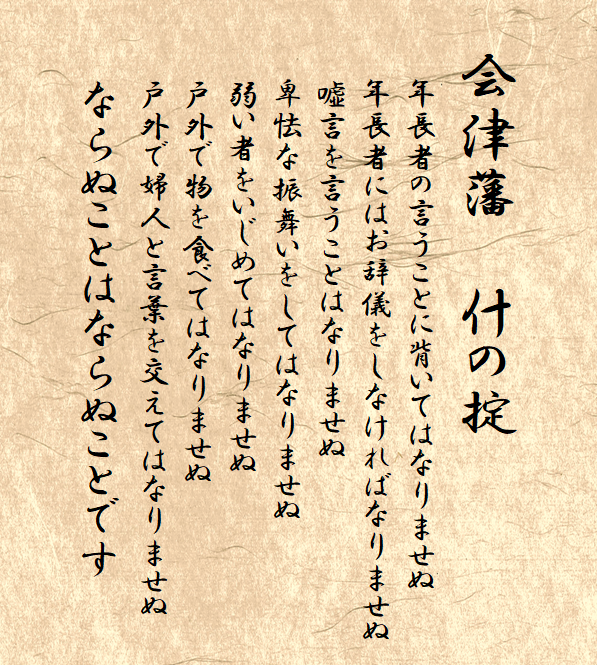

Rules for children of samurai

Before entering Nisshinkan, boys aged 6–9 attended classes in their respective neighborhoods. The children were organized into groups of 10 and were expected to help monitor and regulate each other’s behavior. In preparation for their training at Nisshinkan, they were expected to live according to the “Rules for Samurai Children” (Ju no Okite):

Obey your elders.

Bow to your elders.

Do not lie.

Do not behave in a cowardly manner.

Do not bully those weaker than yourself.

Do not eat on the street.

Do not talk with women outside the home. (This was to discourage interaction with girls and women other than family members.)

Above all: Do not do anything you must not do.

If a boy was thought to have broken one of these rules, he was called before his teacher and peers to explain himself. It was then up to the group as a whole to decide the punishment. The harshest punishment was temporary exclusion, which was viewed with great shame in the group-oriented culture of the samurai. This system of rules and self-governance from a young age encouraged the boys to work together and consider the needs of the group as a whole. With the exception of “do not talk with women outside the home,” these core values are still taught to schoolchildren in Aizu-Wakamatsu.

After touring the Nisshinkan facility, visitors can try their hand at some of the activities the boys practiced, including Japanese archery and the tea ceremony, or paint an akabeko (red cow figurine), a traditional local good-luck charm.

This English-language text was created by the Japan Tourism Agency.